I’m currently editing The Iron Harvest right now. This is the sequel to The Lead Cloak, for those who don’t know. But editing is hard work, so instead of editing, I thought I would write a post on how I edit my novels.

Step One: Finish the book.

You can’t edit a novel until it’s finished. Yes, you can edit chapters and paragraphs, but that is usually just tinkering in the margins. You can’t truly know how a single chapter fits into the book until the whole book is done.

There are people who say “don’t edit” while you write, but in practice I don’t know anyone who has the discipline to actually do this. The compromise I make to myself is this: don’t edit further back than the last chapter. So if you’re working on Chapter 11, feel free to edit Chapter 10 a bit. But don’t go back to Chapter 1. Many writers have an overly-polished first chapter and nothing more. Keep going!

Step Two: Sit on it.

In On Writing, Stephen King says to put a book in a drawer and sit on a book for several months. Long enough that you don’t remember writing the paragraphs when you re-read it. Again, I usually don’t have the patience for that. One or two months is as long as I can hold off before I pick up a book again.

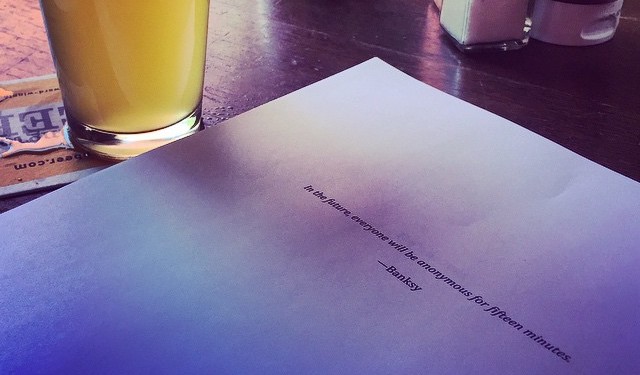

Step Three: Print it.

Print your book. All 300 or 400 pages of it. Double space the lines so there is room for your notes. And make sure there are page numbers (TRUST ME, NUMBER THOSE PAGES! You don’t want to spend time re-sorting pages if your loose-leaf stack of paper takes a tumble.)

I have been sending my books to a local print shop to get printed. The $15 or so is well worth the cost versus draining the toner cartridge on your desktop printer.

You can’t do your first edit on the computer. I can’t stress that enough. You need to print it.

Get a big stack of white paper in front of you and just appreciate how much work went into it. You spent hours and hours in front of a computer screen to make this work, it’s important that—at least this one time—you see it in physical form.

Print it.

Step Four: Read it.

Block off a few hours to read your book all at once. If that’s not feasible, try to read it all within 24 hours. You want to get a full scope of the book and how it all works together (or doesn’t).

During this time, you’re going to find a million little things you want to fix. Certainly add in missing words, change its to it’s, change an unclear pronoun to a proper name, and catch those small things.

But for the big things, don’t fix them. Just flag them.

(This is one reason why printing the book is helpful, it prevents you from being able to edit too much as you read, which slows down the editing process.)

Here are my most common notes when I flag something:

Fix—If something isn’t working, I’ll add a small note to my future self and just write Fix. I almost always know what I mean later.

Unclear—My paragraphs often need to be resorted. Sentences need to be reworked. Instead of trying to untangle them, I flag them.

Bored—Maybe it’s plot, maybe it’s needless description, maybe it’s too much conversation that doesn’t advance the plot. But if the writer is bored, the reader is bored.

Other than that, do your best to enjoy your book as a reader!

Step Five: Write up your big picture thoughts.

On the back of the last page of the book, I usually write up my biggest notes.

These are frequently questions to myself. For example, one of the questions I wrote after reviewing the first draft of The Iron Harvest was “how much of a reminder do readers need of the characters and plot of The Lead Cloak?”

(To be clear, what I actually wrote was “how much reminder of TLC plot/characters?” The notes are just for you. As long as you know things mean, go for brevity in your notes.)

I will also comment on things that did or didn’t work: I think this scene worked, I need to up the tension in that scene, this section moved too slowly, this character didn’t work at all… etc. Another comment I wrote at the end of this book: “I’m rushing at the end.” (This is not uncommon for me, because I’m so excited to finish.)

Step Six: Go through your book.

Back to the computer! New scenes have to be written. Plenty of things have to be deleted (cut and paste big stuff to a second file in case you want it later.) Lots may have to be re-ordered.

This step can take a while. You might end up going through the book several times looking for different things: plot, character arc, clarity of paragraphs, tension at the end of each chapter, writing style.

This is the step many writers jump to, but I think it’s important to go through the preceding steps first. In general: start big, work small. Books and books have been written about this stage, so I can’t cover it all here. Some writers like note cards (check out Marissa Meyer’s process here) and others go with intuition. I map out some things for reference and for other things I go with my gut.

(Possible Step Six A: print and re-read. This depends on how much you’ve revised your book and shaken it out of its original order.)

Step Seven: Share the book.

So, you now have a second draft. It should be a lot better than the first draft. Share this one with friends and beta-readers. If it’s your first novel, you can probably expect your friends and family will tell you what you want to hear, so share more widely than that: a writer’s group, an online critique forum.

Tell people what you want from them in general terms. For example, you might say, “I’m looking for your impressions of the story. Don’t worry about typos, unless you want to flag them, but mostly I want to know what parts you liked, if something bored you or confused you, if a character acts in a way you think doesn’t make sense. That kind of thing.”

Don’t tell them (in advance), “I want to know if the pirate character seems weak.” Because they will come back and tell you that the pirate character seems weak. You want your readers to read the book without any prejudice from you. Ask detailed questions later.

If someone didn’t finish the book, don’t make them feel bad for it. Ask them about the last thing they remember. It might be a good piece of information about where a reader got bored.

Step Eight: Listen to your readers. Or don’t.

Ask readers some questions after their initial opinion. Listen for commonalities between feedback. Do a lot of readers say the same thing? Maybe it’s something to look at. Is one reader really far out in left field from the others? Maybe it’s not worth addressing.

Also, think about the problem behind the problem. If readers tell you a scene doesn’t work, but you really like it, then maybe it’s not that scene that’s the problem. Maybe you should fix an earlier scene that better prepares readers for what’s coming up.

Step Nine: Revise.

What you take and what you don’t from your beta-readers is going to be up to you. Sit on any big decisions for a while before you make them.

Once you make those changes, what you do with your book will depend on your overall plans.

I hire a professional editor for several rounds of edits that sometimes begin concurrently with the beta readers and sometimes begin afterward. Sometimes I hire an editor (or two) for a developmental edit, a copyedit, and at least two sessions of proofreading.

If you aren’t planning to self-publish, this might be the point when you hire someone to proofread the book so that there aren’t any annoying typos when you query it to an agent.

If you are trying to query it and get it traditionally published, I would recommend that you don’t do any further edits that aren’t at the direct request of your agent or editor. You can edit the life out of a book given enough time.

The energy you spend making edits past the third draft is probably better spent writing the next book.